Paddling Just Paddling

(By John Atkinson)

The Oxford Canal is less than ten minutes drive from the house. That means no getting changed by the roadside, just drive down in your trunks and drive back to a shower. You get some looks putting the boat off and on, but there you go, I'll never see the passing drivers again.

On a sunny Friday evening the canal is a place of calm. The heifers drinking by the margins aren't startled by my passing, just vaguely curious. Thanks to the still air, the dust from the bridge works has settled on the surface. As the sun catches it, the glints and sparkles of reflected light are like a snow field. The boat cuts through it like an ice breaker. Silently.

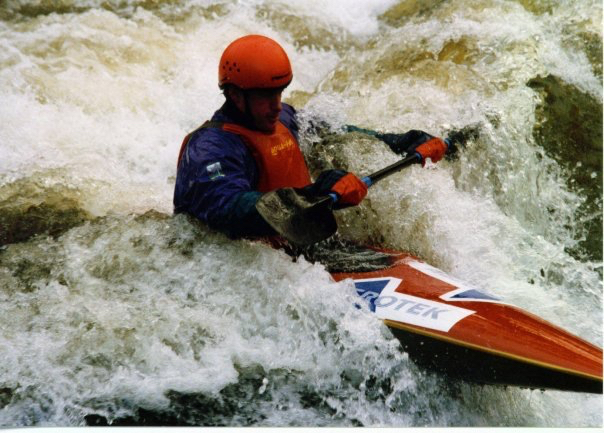

The boat I'm paddling is a slalom boat. It has a carbon shell for a hull with bullet resistant kevlar for the deck. It is thus somewhat over-engineered for the Oxford Canal. But it is the one I've got and after a decade of sitting on garage roofs and in gardens, I'm pleased that it is still dry. Being a slalom boat it is flat-bottomed, it drags through the canal sluggishly. A boat that could feel vibrant and vital in white water seems sullen and sulking. It wants to dance. Even so, an easy swinging paddle stroke moves it on faster than the walker and the narrow boat.

Perfect forward paddling is a zen-like aspiration. The banana shaped hull doesn't want to run true, exacerbated by the short water line. The gentle breeze catches the bow, the paddle and my shoulders teasing the boat off it's line. A one-sided physiology and a feathered paddle leave tendencies for imbalance.

Kayak paddles are off-set by about 90 degrees. It means paddling forward and certainly into the wind there is less resistance. Racers tend to set their paddles just off 90, supposedly to reduce strain on the wrists with the volume of training they must endure. I can't remember how I set these. I notice I'm just clipping the paddle on entry on the left side. I'm not rotating far enough, making a small splash. I focus on it to remove it and it goes.

The broad section of the bow makes a wide wave, a V that defines my route through the canal. As I pass concrete sections of the bank you can hear the wave slap behind you and bounce to hit the stern wave. If I put the boat close but not too close I can feel the lift of the two waves meeting and it offers encouragement to move forward. As I paddle I try to reach over this bow wave as I place the blade. It is solid water to get hold of. I push the boat past the paddle, the blade is not pulled through the water.

In a slalom boat your arms are held high. The skittish nature of the hull needs a stroke close to the rail, parallel to the keel. With the buoyant wide deck this demands a high action. After thirty minutes I feel a tension in my shoulders, I've been holding too high, not relaxed, not swinging through. The paddle is clipped out the water by my hips. I'm paddling slightly long and I can feel the hull just nudging over the wave. I shorten up a little and the boat moves on.

The canal is shallow. Not so shallow that the paddle clips the ground or stirs the gooey mud. But shallow so the boat feels bottom. The wave from the bow travels in three dimensions and when the vertical component bounces off the bed of the canal and hits the stern, the boat drags. It has a tendency for the bow to rise. At times imperceptibly, at times more coarsely I move my weight forwards and back to keep the boat level and running true.

And so for forty minutes I am in a bubble where time and the wider world have gone and all that matters is the synthesis of a body, a boat and a paddle. The bubble pops as I touch the bank to go home. Suddenly I'm tired, I ache and my leg is a pain to get out the flat boat. But just as time stops when I paddle, the time on the water stays with me all day. And I smile and long for my next return to the pursuit of perfect paddling.