Designing Interventions

By John Atkinson

How would you create the conditions that ensured over 1600 dialogues led to Heads of State including their outputs in national pathways? Or that ‘Nature-based solutions’ became an established part of the climate debate? Or that multi-national organisations grew strategies that changed the relationship with their ecosystem? Or that place-based approaches became an established part of how a nation delivered its services?

Each of these required an architecture, a process and a system for orienting those using it. They needed to build on and acknowledge existing circumstances and find the line between providing enough structure to satisfy the aims of a key client whilst allowing sufficient flexibility to maximise local benefit.

The importance of designing approaches in accordance with an understanding of how ecosystems and thus human systems work, cannot be over-stressed. Doing this changes an intervention from an externally imposed approach that will succeed only so long as there as sufficient power and money to shape activity the way you wish, to one that builds a transformational possibility and leaves a legacy of work long after the money and interest has moved elsewhere.

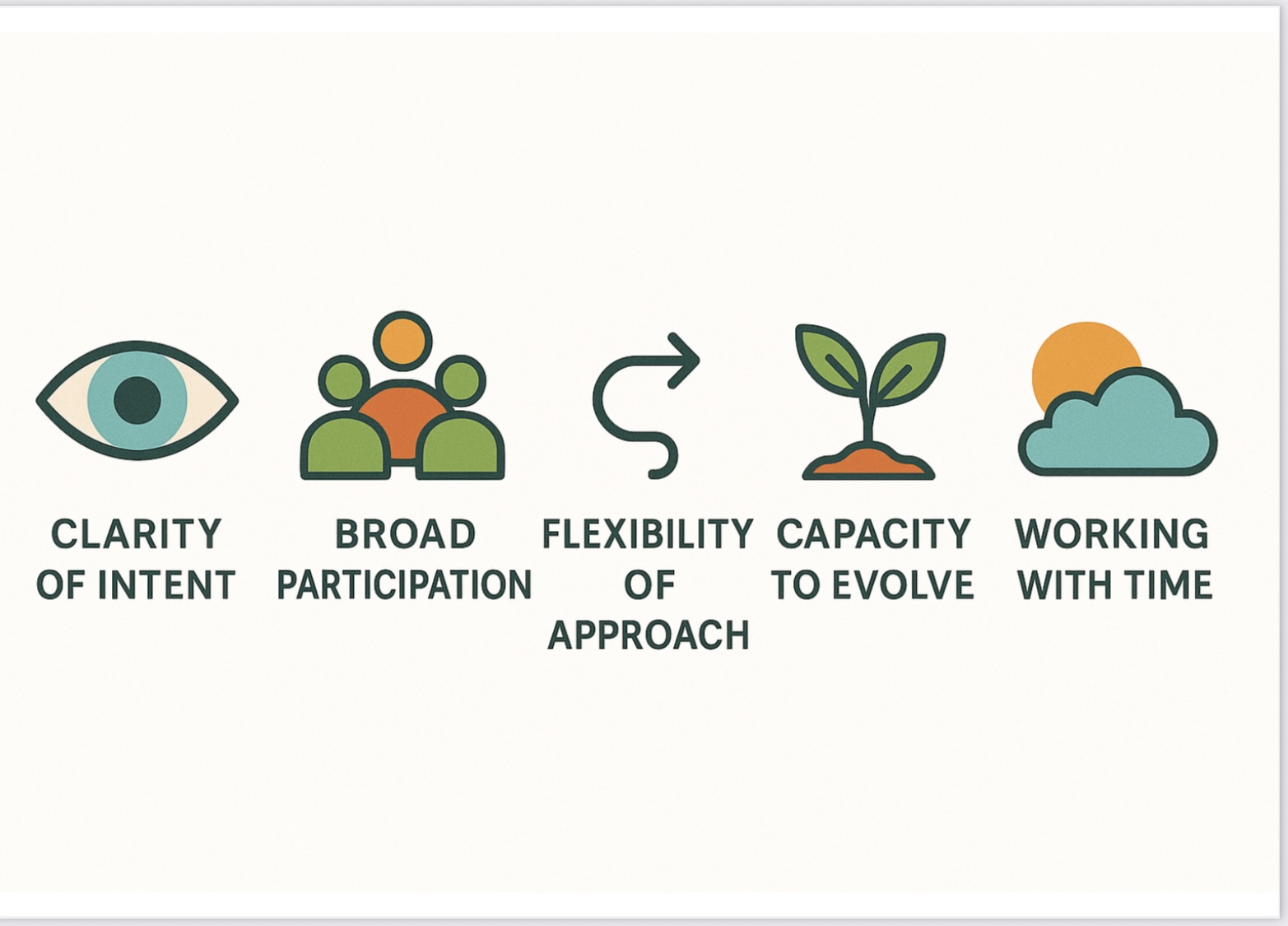

There are five key elements that shape the design of any intervention:

Clarity of intent

In any systems intervention, being clear as to intent defines the scope of the work. It helps people decide if this is something they might engage with and how much of their energy that they will commit. It builds a sense of identity, ‘we’ are the people who are doing ‘this’ work. If it is too tight and controlled it will fail to allow the amplification necessary to allow good ideas to become transformative.

- For the interventions described above, finding clarity of intent provided a common language and identity for participants. It gave people the feeling that they were contributing to a greater good, that this was their opportunity to shift global barriers that had previously limited progress. Clarity of intent builds a sense of identity around the work, shaping the story that helps hold together the inevitable collections of interests.

Broad participation

Complex environments require multiple viewpoints to create an evolved sense of what might be possible. This means attracting a genuinely diverse set of participants. They need to feel welcome, that their views matter, and that they will be heard. They should feel they have agency.

- Great attention should be paid in the design as to how this broad participation can be created. Make it simple for people to engage on their terms, in their place, in their language. Be open and transparent about what you are doing and how. Build in simple feedback loops for people to see how their contributions are being used and where. Be transparent about how collective inputs are being synthesised into new messages. Make it easy for people to do this synthesis for themselves if they wish. Without this, the outputs will lack legitimacy and the mobilisation of people towards achieving them will be diminished and short-lived.

Flexibility of approach

When designing interventions, it is impossible to fully understand the whole range of circumstances within which the intervention will take place. The challenge is to find the balance between sufficient structure that there is a coherent whole, and sufficient flexibility that the approach can be used in all the situations where it is most needed. Being overly dogmatic about your approach alienates people and ultimately excludes their contribution. Being too loose on design means there is no sense of collective identity to the work and the amplification potential is diminished. You don’t need a rigid architecture but there must be a shape.

- The approaches for the interventions mentioned had to contend with a wide variety of local circumstances. Covid-19, conflict, extreme weather and elections all played a part. The approaches had to be able to flex in terms of how people engaged, online, in person, at what scale, and at what physical location. They had to be fluid in timing around key moments without losing sight of the need to maintain momentum.

Capacity to evolve

In any complex environment it is impossible to comprehend the whole variation of conditions that impact on the work. A design made with best knowledge and intent at the start of the work will always be incomplete. It therefore needs built into it a capacity to learn from events and to evolve the approach in the light of this. This evolution needs to be active and considered and to operate in real time. The learning is not simply to be used to tell a story afterwards.

- It is valuable to establish a regular rhythm of interaction whereby people can not only learn about how the work is evolving but can also share their own experiences of what is working, what is not and what they need from the design team to be successful. Putting feedback in the public domain so anyone can view it, ensures the learning process is devolved and not dependent on a central team.

Working with time

Good design recognises the impact of external events and deadlines. There is a constant need to balance the imperatives of short-term requirements and long-term ambitions. Failing to attend to the demands of the day-to-day operation is to create a design that runs in abstract. It risks being fascinating but useless as it becomes detached from the reality of lived experience. On the other hand, losing sight of the bigger purpose is to get captured by ‘business as usual’ and with it lose the potential for transformative impact.

- All the interventions referred to had a hard end point, a budget, global summit or business imperative. Understanding the process by which new approaches can be anchored in processes and architecture is important. Taking advantage of opportunities to consolidate an intervention needs tight and constant attention. Despite the variation in circumstance for example through the impact of Covid, the maintenance of momentum through a series of intermediate points is crucial. Be aware of the natural timing and rhythm of the systems that are being engaged with. Take advantage of them, flex them or ignore them as necessary, but always pay attention to time and timing.

Summary

The act of designing systems interventions requires constant attention. It is a process of evolution not one of control. Never losing sight of the purpose, it is critical to be curious as to what is working and what is not, who is engaging and who isn’t. Not everything will work everywhere so building in feedback loops that enable everyone to learn and adapt as they go is essential. This is how interventions can become transformative. When you allow people to bring all their energy and enthusiasm, when you can hold the inevitable differences and tensions that surface, and when you can create a design that allows people to rapidly learn and expand their impact, you are designing in the conditions for emergence and transformation becomes a real possibility not, simply a buzzword.